|

TV Guide Magazine June 9, 1973 Pages 14-18

|

|

| One Vice President Resigned Because He Was Failing Algebra

Except for such minor setbacks, this Junior Achievement TV project is thriving.

By Clifford Terry

|

TV Guide Magazine Cover

TV Guide Magazine Cover

|

Scene: A hospital room. "I don't understand it,” the doctor says to the nurse. "Sixty-two years of performing tonsillectomies. This has never happened before - McMahon's Syndrome. It happens once in 10 million cases and it happened to me--to him." He points to the patient. Just then the man's family enters. "Good Lord," the doctor sighs.

"Doctor, you'll have to tell them eventually," the nurse whispers '"They're sure to notice the change."

"Mrs. Darwin," the doctor begins. "You're going to notice a slight change in your son since his tonsitlectomy. But it's merely superficial. Inside, he's..."

The mother pulls back the bedcovers, looks at her son and screams. "McMahon's Syndrome" it turns out causes one's head to be turned into a cabbage.

Eugene lonesco? Samuel Becken? Bob and Ray?

None of the above. This bit of nonsense soap-opera parody entitled 'Love of Lust' is being performed under the sponsorship of Junior Achievement, Inc., the do-it-yourself economic-education program for high school students that usually is more associated with manufacturing clothes hangers and bird feeders than it is with exploring potential cabbage-head malpractice suits.

Every Saturday morning for 15 weeks 25 to 30 teenagers assemble in the studios of WNDU-TV, an NBC affiliate in South Bend, Ind., on the campus of the University of Notre Dame. There, just a couple of long punt returns from the famous football stadium, they video tape a student-created and produced satirical program, Beyond Our Control.

Now in its sixth season and seen in the South Bend area at 6 P.M. Saturdays from late January to mid- May, the show features such bits as spoofs of daytime game shows (The Nearly-Wed Game), horror movies ("The Rancid Hunk in the Girls' Dormitory"), highbrow movies (Francois Triffles' "Les Mohicans Terminal"), and the inevitable soaps (‘As the World Squirms’). There has been a Soviet dance party, Communist Bandstand (sponsored by Iron Curtain Cleaners). and The Porter Mulehole Show from Trashville, Tenn, featuring a performer named Charlie Shame singing his big hit, "A little bit lonesome/A little bit blue/I'm cleanin' my rifle/And dreamin' of you."

Local shows are a particular source of devilish delight, too, parodied through a "low-budget, big-idea" archetypical station, WIMP, which predicts election- night results with 1/10 of 1/100 of 1 per cent of one precinct reporting, or displays a group of politicians yawning, staring off into space, and occasionally discussing such hard-hitting topics as township reapportionment.

Teen-agers being teen-agers, the titles of the spoofs often are funnier than the material that follows, with the over-all results, according to WNDU director Mark Heller, who works with the JA kids, as uneven as a 16-year- old's complexion.

|

Besides Heller and a few technical engineers, the show is the responsibility of the high-schoolers, who write the scripts, operate the cameras and video-tape machines, shoot 16-mm film and frame-by-frame animations, and sell the commercial spots. "They're so skillful and sophisticated, I'm constantly stunned," says Dave Williams, WNDU promotion manager and senior advisor to the JA program. "You don't find too many TV production companies where your vice president in charge of sales has to resign because he's failing algebra."

|

Steve Hawks, Geoff Roth

Steve Hawks, Geoff Roth

in Happy Smiley News.

|

In its first years the student company (WJA-TV), formed in 1960, was a bit of a bomb, uneasily evolving from a teen-age amateur showcase to a quiz show. In 1968 a change was called for. "We didn't want a miniature Ed Sullivan Show," Williams recalls, "or four people sitting around a coffee table rapping about the relevant issues of the day." The result was a kind of "Mad Magazine of the Air," which may be the only one of its kind. "This is an extremely ambitious project," says director Heller.

"We learn about the technical aspects and the writing of scripts, but more than anything, it's just fun," says Diane Werts, a junior at St, Joseph's High School in South Bend, if it is fun, it is also time-consuming. "My panents are always remarking, 'We never see you -- where are you all the time?' says Julie Ratkiewicz, who was impeached last fall as president of her La Salle High School drama club for spending too much time on cabbage heads and not enough on drama.

|

The group is selected each year through a process that includes recruitment ads on TV and in school newspapers, awareness-seeking interviews and tests. A thorough indoctrination program follows ("They're very casual about operating $75,000 color cameras and $90,000 video - tape recorders," Williams says), and a handbook is distributed which contains such advice as "Avoid and help discourage what spinster English teachers generally refer to as 'horseplay'..."

About 8 to 10 per cent of the students intend to make broadcasting a career (the show's alumni indude a radio sportscaster and a disc jockey), but most are doing it for fun. Sometimes it isn't. The scripts are written by half-a-dozen hard-core members, who meet at an adviser's house four nights a week to come up with, hopefully, 20 to 23 minutes of fresh, zippy material to be pumped into 15 taping sessions and then winnowed down into 12 half-hour programs, capped by a season-end, hour-long special of highlights.

|

Production manager Dave Bashover and one of his cameramen.

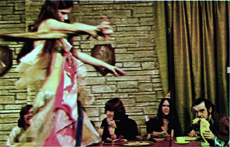

Whirling dervish Teri Jacobs, performing the "Dance of the

Seven Veils." |

Often, the teens get their first professional taste of writer's block, which results in reruns. "The thing we hold over their heads," says Williams, "is that we have to produce a show every week, and if there isn't enough material, then we have to dip into the archives. They hate that with a passion."

Quite predictably and understandably, one of the show's top targets is the insipid commercial. The result: products such as Semi-Coma sleeping pills, a doll named Dolly Drop-Dead, her friend, Larry Laser ("with the built-in industrial-strength laser beam imagine the fun you'll have the next time Mom smarts off at you"), and a house in "beautiful Sherlock Homes, the project with a near-by golf course, swimming pool, and picturesque copper-smelting plant."

Surprising, perhaps, is the dearth of political material. (The consensus seems to be that politicians have nothing new to say.) An exception was a WIMP election special, "Mare for Mayor" --puff coverage of a machine-controlled candidate, William Jennings Mare. (" ... born in a small log cabin where he learned to split hairs and burn books by a fire. His ambition is to bring up his family in a city where they can walk the streets at night without being spit on. . . . He makes his own clothes, and is known to the kids in the neighborhood as 'Sir'.")

Good material apparently overrides the bad, and the program attracts a dedicated, if small, following. (According to ARB's averages, it is seen in some 13,000 homes in the 75-mile radius area, compared with 33,000 watching Wide World ot Sports.)

About 90 per cent of the mail is favorable, although complaints of "disrespect" were lodged when the Winter Olympics was parodied (events included uphill skiing and the 400-kilowatt chaise-longue competition). In addition to the inevitable anonymous notes about the "hippie kids" and "smelly show," a tavern owner once threatened the show with a lawsuit when his place was inadvertently included in a mock tour- guide of South Bend's seediest joints.

Show business being a business, Beyond Our Control is subject to Junior Achievement guidelines, under which officers are elected, stock sold for $1 a share, and the students paid 25 cents an hour and given bonus points which later translate into cash. Every year, even after paying off 25- cent dividends, the satirical show has provided a slight profit.

The yearly budget is about $4,500, of which 70 percent is paid to the NBC affiliate for a special-rate rental. "Most stations give away their facilities to JA groups," notes Dave Williams. "But we try to make it as realistic as possible." To finance their efforts, the students must sell 180 commercial spots at premium local rates ($61 for 60 seconds, $45 for 80), for which they receive 3 1/2 to 7 percent commissions.

Sponsors range from bowling alleys and motorcycle dealers to Bell Telephone and Coca-Cola. "The main idea we try to get across is that our advertising will help them," says salesman Mark Cybulski. "We're not looking for charity." Most potential advertisers are polite, if nothing else, but one yelled into the phone, "Communists!" and then hung up.

The irony, of course, is apparent. Junior Achievement is about as far left as the Junior Prom.

The straight-shooting image is such, in fact, that most of the TV group would like to dissociate themselves from it as much as possible, "We like JA because that's why we're here," hedges one. Adds another: "We really try to get on a good basis with the other JA companies. but I mean-coat hangers! "Yecch!"

TV GUIDE JUNE 9 1973 |

|

|

|

|

|

|