"Beyond Our Control," an unusual local television program produced by high school students, is concluding its sixth successful season on television. The project has evolved from rather shaky origins into one of the nation's most widely-acclaimed high school television projects. It is a weekly satirical revue, conglomeration of comedy, music and experimental films about TV that runs for about half an hour. Much of the programs impact comes from its imaginative sequences filmed with our faithful Bolex Rex IV. Our Bolex has been cleaned and lubricated, been repaired once (following an nasty incident with a collapsing tripod), had a Rex-O-Fader attached... but it's basically the same, reliable workhorse we got six years ago. The camera crew is different, however. Now the students themselves are shooting all the film. The project began in 1960 by a nationwide economic education organization known as Junior Achievement. JA is devoted to giving high school students a first hand, learn-by-doing introduction to the American system of free enterprise by enabling them to operate their own model corporations. In 1960, the South Bend, Indiana, JA Director approached William Thomas Hamilton, Executive Vice President of the WNDU stations, with a plan to form a student-operated television production company. WNDU-TV is a somewhat unusual television station. Owned by the University of Notre Dame, the station is an NBC network affiliate, a tax-paying commercial corporation. But the television station also exists to function as a department of the University in teaching Communication Arts. Thus, the high-school television project struck Hamilton as a unique way of extending the station's educational aims to the secondary school level. In 1961, the first student company took to the air with a 13-week series of half-hour shows. The students had sold stock to raise operating capital, leased studio facilities from WNDU-TV, created a program format, and sold commercial advertising within the show to finance the venture. Pronounced a success, the company - known as WJA-TV - continued, largely concentrating on the production of relatively simple game shows, including local versions of charades, quiz games, and the like. Then in 1967, advisers to the project felt that the time had come for change. Students now in their teens had grown up with television as a babysitter, instructor and constant companions. Somehow, the thought of doing yet another game show was not proven to be a strong attraction to a broadcasting career. The advisers crossed their fingers and elected to produce something a bit more challenging.

What emerged was "Beyond Our Control"... in more ways than one. The title comes from the familiar broadcasters' admission of problems "Due to circumstances beyond our control". The show deals with the foibles of American culture. And what could be a better mirror of our culture than television, itself. In a given week, items "beyond our control" might include TV soap operas, pollution, politics, high school pep rallies, rock music, detergent commercials, underground movies and much more. As the years passed, the program format underwent considerable refinement. From a modified TV variety show complete with hosts, local talent, and comedy skits - the show transformed itself into a fast paced, multi-faceted mixture of parody, satire, humorous music and experimental film. And the viewers have responded enthusiastically. The show received hundreds of fan letters from throughout WNDU TV's 28 county coverage area - more line than any other program. The show's ratings doubled in the last year, and the program has been a commercial success for the past two years. Most important, in keeping with the project's educational goals, more and more of the production tasks have been turned over to the students, including television camera operation, audio engineering, videotape operations and 16mm filming with our Bolex. "Beyond Our Control" begins each year by recruiting high school students in September. A membership committee composed of advisers to the project from the staff of WNDU-TV and top students returning to the company from the previous year interviews each applicant and forms a company of 25 to 30 members. Orientation sessions follow, describing the history of the project, its goals and production techniques, studio procedures and organization plan to the new members. All members sell stock (at $1.00 per share) to raise operating capital for the budding the venture and elect corporate officers. By October, a small portion of the company has begun to meet regularly to write the original material for the programs, and a few weeks later, the company moves into WNDU-TV's campus studio for orientation sessions. Working with a WNDU director, they learn the basics of television camera operation.

| | Page 1

|

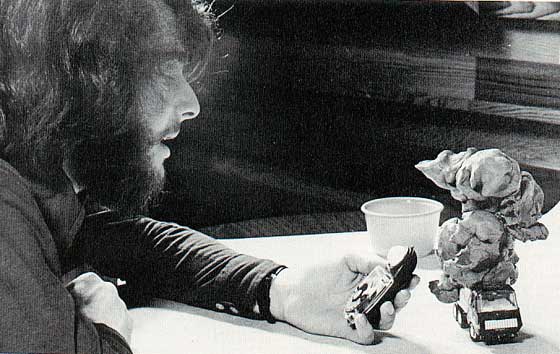

Production manager Dave Bashover takes an exposure reading prior to shooting one of the twelve clay animation sequences used on Beyond Our Control. (The producers noted with some amusement that the small dump truck received more fanmail than any human member of the cast.) | | Other students work with "Beyond Our Control" veterans to learn videotape recorder operation, audio engineering, announcing, audio tape make-up and other technical skills. By late November, the students are ready for a practical trial. At the addition session, everyone has an opportunity to perform in front of the camera and practice behind-the-scenes skills. Actual production of the program begins in December. The program is videotaped Saturday mornings, with a set up crew were writing at 7:00 a.m.. The balance of the company arrives at 8:00 a.m. for an exhausting five-hour production session. One outside observer wrote: "It was an amazing scene, about 30 high-school students were scurrying all over the place, lifting sets here, aranging cameras there. Dave Bashover, the high school senior in charge of managing production, was hurling orders like a pro, and efficiently prevailed." In the course of the year, 12 original half-hour shows are produced, telecast Saturday evenings at 6:00 p.m. beginning in late January. The final show each season it is a one hour special, reviewing the year's highlights. The Bolex Rex IV enters the picture early in the year as we get ready to create the film sequences which occupy 25 to 30 percent of the "Beyond Our Control" show. We use film for animation, special effects, on-location work, clay modeling sequences and major skits. The viewers lavish much of the written praise on these film sequences.

An animated film titled "Emissary" was described by one viewer as "...brilliant in many of its sections." A clay modeling animation technique used to introduce our commercial breaks brought this comment: "I really enjoy the efforts of your chief animation photographer; the clay and dump truck episodes our great." And a parody of an outdoor theater intermission film was described as "...fantastic... a stroke of genius."

The producers are loathe to disagree. Early in the year, the students are offered some basic instruction on filmmaking technique. The rudiments of exposure, indoor lighting, focus, and specific technical operation of the Bolex itself are covered, together with the rundown of the basic animation techniques we regularly use. At the beginning of the year, I show much of the film, letting our Production Manager, a high school senior, pick up the techniques largely through osmosis. After a few months, he borrowed the Rex IV instruction manual and pronounced himself ready to take over. With only a few misgivings, I turned the camera over to him. After shooting the film for so many years, it was an odd sensation to sit on the sidelines, offering only occasional suggestions, double checking an exposure reading or helping set up a lighting unit. The results, from the very first reel, more than justified his confidence, and since that time, 99% of all our filming has been in the hands of the students. The single-frame capabilities of the Rex IV, together with its variable shutter, backwind, reflex viewing and focusing through the lens, and the wide range of film speeds, makes it an ideal production camera for our unusual needs. We shoot Ektrachrome 7242, filtered for daylight, which is processed on the premises by the WNDU News Department. Since we have no recourse to laboratory printing for special effects, everything must be done in the camera: and that's where the Bolex shines. Fade-outs, fade-ins, lap dissolves, slow and fast motion - they're all within our capability and are used regularly. With reflex viewing, the Bolex can shoot titles and extreme close-up quickly and accurately. And the camera's ability to single-frame with steady registration and accurate exposure is put to use almost constantly. At our peak of production, the Bolex was in use three to four days every week.

| | Page 2

|  | | Members of the Beyond Our Control company man the videotape recorders at a Saturday morning production session. Doubling as a technician is the company's Vice President of Sales, Geoff Roth. Diane Werts, the Assistant to the Director is in the background. | | The silent film is edited by the students Thursday evenings each week. When the program is produced on Saturday mornings, the soundtracks are dubbed in as the film is recorded on videotape. Since lip-synch sound is not practical, we have developed a number of techniques to add sound to our film. Each year, we do an old-fashined silent movie (usually shot at 12 fps), adding tinkling piano accompaniment. Other films are planned so that music and sound effects enhance the visuals sufficiently to make dialogue unnecessary, and still other films are simple voice over narration. Another good dodge was employed when we produced "Hercules and the Hard Job," a bogus made-in-Italy muscleman movie; we felt justified in dubbing in dialogue rather haphazardly since lips sync in those films is notoriosuly flawed. As the students came up with new ideas each week, we grew increasingly appreciative of the Bolex's versatility. Few of our wild schemes proved beyond the Rex IV's capabilities.

For example, our program opening each week employed a kinestasis technique of shooting large numbers of still pictures of motion picture film in brief 4-frame segments, exposing single frames. When projected at the standard 24 frames per second, the pictures deliver a sensory barrage. On first viewing, many of the individual photos cannot be recognized, but an overall impression of the subject matter is perceived. On successive viewings, more and more details become evident, rendering the film interesting over repeated viewings. In our case, the kinestasis technique sought to capsulize American culture - much as the program itself would. Using ultra-close-ups and lap dissolves at the outset, the film focuses on a hand switching on a TV set, tubes glowing and the TV screen flickering; then the screen dissolves into the chemist basis sequence; from detergent boxes to the Vietnam War, contemporary movies to political headlines, rock music stars to TV personalities. All race by at six pictures per second. The sequence was shot by the Bolex mounted on a modest title stand over a period of two days, largely in the author's living room, which was ankle deep in books, magazines, snapshots, pamphlets and small objects representative of our culture. Nearly 400 separate subjects were photographed, and we exposed over 1,400 frames of film one by one. To ensure that no splices would distract from the film, we insisted that it be shot in one long take; fortunately for our sanity, the first take was flawless. The first time the Bolex was ever turned over to students was in 1972 when production manager Kim Guidi shot most of the film for an extremely popular story titled "Jacks." Flapjacks, actually. In the story, a woman using a package of "Extra Lively" panckake mix drops a flapjack to the kitchen floor; when she looks down, it scurries away. (the action, of course, is acheived by moving the object, inch-by-inch, between single-frame exposures with the camera secured on a tripod.) More and more live pancakes invade the house, appearing in corners and under the sink like mice. The distraught family sets up mousetraps to catch the pancakes, and a small war develops, with the pancakes busily moving furniture about, setting their own traps, and eventually dispatching the family. In the final scene, the jacks are moving on to conquer another house. Having done animation films like this for several years, we have worked out most of the bugs and can offer some advice gain through painful experience:

• Once the camera is set, mark the edge of the frame (as seen through the viewfinder) with masking tape. This serves as a guide to the animator moving the object between exposures, insuring that he is out of the shot when the shutter is released.

• Watch the background for shadows. Even when the animator moves out of the frame, he may cast annoying shadows on the background.

• When working outdoors, keep an eye out for changes in the lighting. The natural motion of the sun and passing clouds may alter exposure enough to ruin a sequence. And, if it takes very long to shoot the animation sequence, watch for moving shadows caused by the sun's changing angle.

• Try to stage animation sequences on steady, hard surfaces. Avoid surfaces like shag carpeting; as the animators step in and out between exposures, they crush the pile. The result is a carpet that has ocean waves when the film is projected.

• Small pieces of clay like caulking cord can be used it to temporarily secure stationary objects during long animation sequences, rendering them less likely to be bumped during the filming. The clay cleans up reasonably well

• If there is no way to prop up an object at an angle without its falling over, try using thread or nylon fishing line. If it is only used in a few frames, it is rarely seen by the viewer.

• In a single shot, try to avoid mixing single-frame exposures and continuous-run exposures; changing the apeture in the middle of the scene to make the change almost always shows up.

• If an object is bumped or the sequence spoiled by someone's arm getting caught in the frame during exposure, the sequence can often be salvaged by cutting to a new angle or close-up and picking up the animation were you left off, the offending frame being removed in editing.

The same basic techniques are used for our popular Intermissions sequence. Parodying outdoor theater intermission trailers, we used popcorn boxes, ice cream bars, wieners and soft drink glasses dancing around at the huge papier-mache and plaster mouth, built by our assistant production manager Keith Kepler. The food dances about, and then moves up a ramp - airplane boarding style - and leaps into the mouth. After a few shoes, the mouth opens up for lost the Burke, the sequence runs 45 seconds and took about three hours to shoot. Aside from spilled soft drink cups and a mouth that refused to stay open, the chief problem was the ripe odor of the food after three hours under the lights. A few shots of Lysol took care of that problem. Probably the biggest success of the year was a series of 12 films used to introduce our commercial pauses. Created by Dave Bashover, the 15 second films each took over three hours to produce. The format was the same: a miniature dump truck rolls in (animated single frame, of course), deposits a load of modeling clay and exits. The clay that appears to mold itself into familiar objects, the actual modeling taking place between exposures. Following the commercials, the dump trucks returns, picks up the clay and exits. With the Bolex's rock-steady registration, the resulting animation sequences are smooth and fascinating to watch. In addition to molding the clay, Dave introduced other objects into the models (between exposures) as he worked. Thus, we could form a clay egg, break it open, and have a real egg yolk emerge. A beer keg with a spigot was formed from a lump of clay and when the spigot was turned on, the beer flowed. The clay molded itself into light socket, with a working electrical socket inserted between frames; an electric light bulb was screwed into the clay socket and switched on. The brief segments drew so much favorable comment that we were prompted to produce an eight minute film using the technique for the season's final show. "Emissary" tells the story of a small visitor from a small planet... a (clay) figuring capable of altering its shape and passing through solid matter. The humourous story details the problems encountered by the visitor as he tries to make contact with a human fmaily, transforming himself into familiar objects in an attempt to make himself presentable. "Emissary" was shot on a crash basis in our last two weeks of production, occasioning some late hours and raising some parental eyebrows for the crew. But the overwhelming response made it worth the extra effort. All long more normal lines, we shot a silent movie serial based on the adventures of a mythical St. Mohab; a parody of a preview for the typical beach party movie; an underground movie spoof titled "Look Me In The I;" a take-off on Japanese monster movies; an action epic titled "Sgt. Yukon of the Yukon;" and numerous television commercials both real and humorous.

| A scene from a silent movie produced by the company, showing the Pharaoh's daugheter clutching the infant "St. Mohab." |

"Beyond Our Control" has, after six years, firmly established itself in the market as a genuinely unique example of local programming. Its reputation would probably be considerable if it were produced by the regular production staff of the station; the fact that it is produced by high-school students makes it all for more unusual. Viewers are genuinely enthusiastic in their mail to the show: "really fantastic", "the funniest show on TV", "probably the only real entertaining show on TV this week", "a Saturday night must", "the best show we watch all week". Wrote the student magazine Scholastic: "some of the best writing on television... a stunning display of satire at its best". And a somewhat younger fan wrote: "I love your show. I hope he can show it for years to my children will get to see it. I'm only 11 years old, but I'll grow". And what's fun for viewers is also fun for the students involved. Responding to our annual year-end evaluation questionnaire, more than half the members of the company had comments typified by this: "It is the most worthwhile thing I've done in my life." Editor's note: The 1973 edition of WJA-TV was awarded a George Washington Honor Metal by the Freedoms Foundation of Valley Forge in the Economics Education competition, and for program quality, the program was named the Best Locally Produced Variety Show [for markets under the top 25] by the National Association of Television Program Executives.

| | | | |